By Lawrence Williams

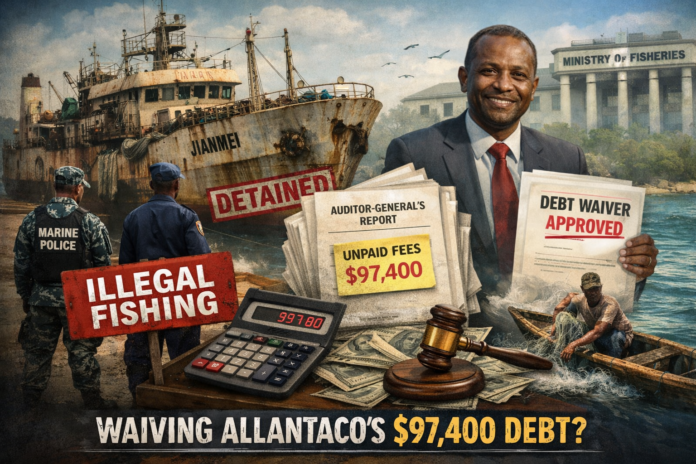

The Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources is facing renewed scrutiny after the Auditor-General’s 2024 report revealed unrecovered licence fees, unpaid fines and regulatory inconsistencies that could cost the government hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost revenue.

At the centre of the findings is Allantaco Fishing Company, whose vessel Jianmei was arrested and detained for illegal fishing within the inshore exclusion zone (IEZ) — an area legally reserved for artisanal fishers — and for failing to pay outstanding licence fees.

According to the report, the vessel owed $93,900 in licence fees and $3,500 in fines, bringing the total outstanding amount to $97,400. Despite the seriousness of the offence and the vessel’s detention, auditors found no evidence that the money was ever paid, nor any concrete recovery action taken by the ministry.

The report stated that failure to recover the outstanding sums could deprive the government of “much-needed revenue,” particularly in a sector that is already under pressure from illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

In response, the ministry told the auditors that they had sought and obtained a cabinet approval to waive all outstanding arrears owed to the Ministry of Fisheries, including those owed by Allantaco Fishing Company, saying it’s part of their efforts to “boost confidence and investment in the fisheries sector.”

However, the auditors noted that the said cabinet approval was not submitted for verification, leaving the matter unresolved.

Moreover, this disclosure raises critical public-interest questions, such as why would the ministry seek to waive substantial arrears owed by a company whose vessel was arrested for breaching fishing laws and encroaching on protected inshore waters. Another concern is how does such a waiver align with the ministry’s statutory role as the chief enforcer of fisheries regulations and protector of coastal livelihoods.

For artisanal fishing communities, illegal fishing in the IEZ is not only a violation but also a direct threat to food security and income. Critics have always argued that waiving penalties for offending industrial vessels risks sending a signal that compliance is negotiable, especially for well-resourced operators.

The auditor-general also identified systemic weaknesses in the ministry’s handling of licence fees and royalties.

Auditors found inconsistencies in licence and royalty assessments, contrary to the Finance Act 2020, resulting in a revenue shortfall of $101,414, which comprises $76,094 in licence fees and $25,320 in royalties.

The ministry responded by saying that some fishing companies were issued one-month licences to test new or refurbished vessels, instead of receiving free test licences, and claimed this resulted in “no financial loss” to the government.

But the auditor-general rejected this explanation, pointing out that the Finance Act requires industrial fishing licences to be issued for a minimum of three months, not one. As a result, the audit concluded that the ministry did not comply with the law, and the issue again remains unresolved.

The auditor-general has recommended that the permanent secretary and acting director of fisheries recover the outstanding sums from fishing companies, including Allantaco. Whether those recommendations will be acted upon or quietly overridden through waivers remains a key test of government commitment to accountability, and the protection of Sierra Leone’s marine resources.

As pressure mounts to curb illegal fishing and strengthen public finance management, the unanswered questions surrounding the proposed cabinet waiver are likely to intensify calls for parliamentary oversight and public disclosure.